I Called Him Morgan (Sweden 2016, director Kasper Collin), Vancity Theatre screenings Friday, June 2, 8:30 p.m., Monday, June 5, 8:30 p.m., Wednesday, June 7, 6:30 p.m. and Thursday, June 8, 6:30 p.m. as part of Jazz on Film series leading up to this year’s TD Vancouver International Jazz Festival, June 22 to July 2 (coastaljazz.ca/jazz_on_film).

Kasper Collin’s brilliant documentary about the life and tragic death of the great jazz trumpeter Lee Morgan is returning to the Vancity Theatre for an encore performance as part of the Jazz on Film series.

I Called Him Morgan received its world premiere at the Venice Film Festival in September 2016 and then hit the festival circuit (including Telluride, Toronto, New York and Vancouver) the following month.

After the screening in New York Richard Brody wrote in the New Yorker, “Collin builds ... a revelatory and moving portrait of a great musician and the other great people, whether celebrated (like musicians with whom Lee Morgan performed) or unheralded (like his common-law wife Helen), on whom his art and his life depended. It’s both a portrait of people and a historical landscape, a virtual vision of American times – the lives of black Americans in the age of Jim Crow and de-facto discrimination in the North – and of the artistry and personal style that arose in response to them.”

A hard bop contemporary of Miles Davis, Morgan first made a name for himself as a teenager working in Dizzy Gillespie’s band before moving on to Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers.

He released his first album as a leader, Lee Morgan Indeed!, on the Blue Note label in 1957.

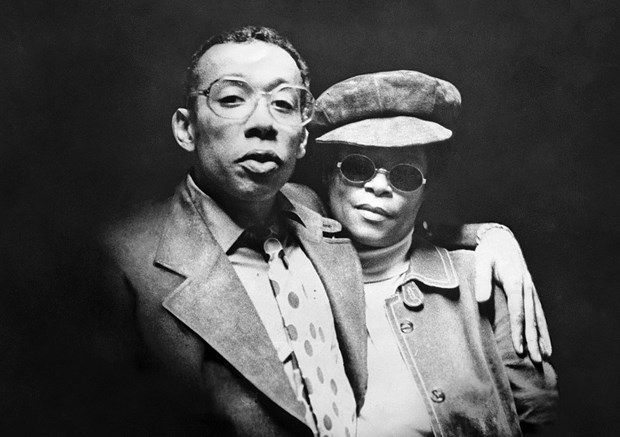

A debilitating addiction to heroin dogged Morgan for much of his professional life. When Helen Morgan first met him one New York winter’s day he had no coat, no shoes and no instrument, having pawned everything he had to feed his habit.

She turned his life around. Gave him some food, a place to stay and ultimately became his business manager.

Despite his hardscrabble lifestyle Morgan was one of the most recorded artists on the Blue Note label through the ’60s with Helen credited in helping him get his life back on track. And then she took it all away one February night at Slug’s Saloon in 1972.

The gunshot shouldn’t have killed Morgan but there was so much snow on the streets of the Lower East Side that night the ambulance took forever to get there. He bled to death.

Winter plays a big part in Morgan’s story with cinematographer Bradford Young’s opening 16mm shots of snow flakes coming down on a cold New York night setting the cinematic mood.

Collin talked to the North Shore News the day after he first screened the film in New York City where many of Morgan’s friends and colleagues were in attendance.

North Shore News: Jazz and film are two very specialized topics. How did you put the two together and get involved in making jazz films?

Kasper Collin: I’m very music oriented. I love music almost more than anything. It’s been very important in my life. I made another documentary before this, called My Name is Albert Ayler, which was about a jazz musician. That film took seven years for me to make. That was my first feature documentary. I was finished in 2005 and I remember after making that film – because it is quite an endeavour to make those kinds of films and they can take a very long time – I thought I probably would not make a documentary like that again. I worked on some other projects but then seven years ago I was watching YouTube and I found this incredible clip of Lee Morgan playing with Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers in 1961. They were performing Bobby Timmons’ – the piano player’s – composition “Dat Dere” and there was a Lee solo in there that moved me deeply. I kept watching it over and over for many days. I realized then that Lee Morgan was really something very special. I started to play around with the idea that there was maybe a film there. The research developed into the film we have now.

North Shore News: Both your jazz documentaries deal with musicians whose lives were cut short.

Kasper Collin: I must say I didn’t know much about Lee Morgan when I first saw the clip on YouTube. That came after actually. With Albert I knew more when I started. When I do these kinds of projects they take a long time. I’m doing it from passion and I’m coming from the music side. It all started with me discovering this very talented musician and the sound of his horn and his phrasing. That was the start of it for me. I only knew about Lee earlier from his album The Sidewinder and of course I had been listening to a lot of musicians in the Blue Note catalogue. Because I’m coming a little bit more from the experimental side, improvisational and free jazz The Sidewinder was not really a record I (listened to) but when I saw Lee in this clip I discovered a new Morgan. I started listening to his music and found a lot of incredible stuff. It starts with the music and my passion for it.

North Shore News: What was involved in researching the material for the film?

Kasper Collin: You’ve got to try and see if there is a possibility to make a film. You have to find how much material exists. That was one of the fascinating things about Lee because there were so many people that knew him and were still around. I started to do some interviews with people that were close to Lee and that was special for me because I knew about The Sidewinder and I knew about a woman had shot him but I didn’t know anything about her – that is something you could read in Wikipedia but no one seemed to know who she was. They immediately started to talk about Lee’s last four years and they started to talk about Helen and what a lovely person she had been and how much she had helped him. They said she had saved him from his addiction and helped him to get over that. That was something I didn’t know about – I only knew her as the woman who killed him. That opened up a new dimension to the project. Those guys really wanted to talk about those last four years. It was something that was important for them in their lives and the project sort of navigated toward that relationship story between Morgan and Helen.

North Shore News: Larry Reni Thomas’ cassette tape is an incredible document in itself. If he hadn’t interviewed Helen the story we know would be quite different.

Kasper Collin: I got in contact with him and got a chance to listen to the tape. He made a copy of it I think in 2009. That’s an extremely important document for the film. I didn’t know in the beginning exactly how I was going to use it but the more people I met I realized it would (need to be part of the film). It’s fantastic material. Also fantastic to find were the still photos. I knew about Blue Note and Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff, the two German guys that founded it, and I knew Francis was an excellent photographer but I had no idea how many photographs he actually took. Lee Morgan was one of the most recorded artists on Blue Note along with Hank Mobley. I went to the photo archive thinking I would find some nice photos to use. Lee Morgan started to record for Blue Note in 1956 when he was 18 years old. They covered every session with still photos. Lee was documented up to 1967 in black and white pictures and after that in coloured slides. There were 165 negative black and white sets I could find in the archives from different sessions with Morgan. Almost 2,000 still photos documenting those years in his life – just incredible material to work with. I made copies of the shots and took them home to Sweden. I had an assistant who scanned them and we made enlargements of them. This was an important part of the editing process. I remember me and one of the editors were editing in her apartment and we spread a lot of the photographs out on her living room floor and we were just crawling around because you could really see those amazing stories and episodes within those negative sheets. The photographs are so special because you can see the love and the joy and the communion between the musicians. I worked a lot with the photos and tried to use them in the best possible way within the film.

North Shore News: It’s amazing that Lee could function with all the drug problems he had. Helen gets a lot of the credit for pulling him back together.

Kasper Collin: He was really down and out and they met around 1967. She helped him back. Those last records that he made Live at the Lighthouse and the posthumous recording (The Last Session) – that’s really amazing music that he’s giving to us. She was extremely important in helping him get back on the scene again.

North Shore News: Her story also, in a general sense, touches on the postwar migration of southern black culture north into urban centres. As a teenager she moved from a North Carolina farm to New York City to make her own way in the world. Quite different surroundings from what she was accustomed to.

Kasper Collin: She grew up in the southern U.S. and had her first children at 13 and 14. She just decided to go away and somehow got to New York and created another life. She actually became Lee Morgan’s manager. It’s quite a journey she makes. Then a tragic thing occurs and she kills Lee Morgan and returns to the south again. The film follows her story as well. The film is about Lee Morgan and Helen and about the music that brought these two people together.

North Shore News: Who was at the screening in New York?

Kasper Collin: There was a lot of people there from the fllm – Billy Harper, Paul West, Larry Reni Thomas, Larry Ridley – Reggie Workman, he was not in the film but he was someone who was close to Lee. I’m probably forgetting somebody. It was a very special evening with a long Q and A at the end.

North Shore News: In the film it’s great to hear Wayne Shorter’s take on everything. He knew Lee from very early on.

Kasper Collin: I really wanted him to be part of this film because I knew how close Lee and he had been when he was really developing as an artist in Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers. Wayne rarely speaks about his relationship with Lee. It took me four years to get him on board. At first we were trying to edit the film without him but when we had him it was so great because he is talking about Lee as an artist on the same level as he is.