Forty-eight years after a North Vancouver educational experiment ended, an emotional reunion in early June brought together students from a gifted program called “Major Works” at Brooksbank Elementary.

In 1969, Scott Thompson was one of the students who was tested in Grade 3 at his home school of Burrardview Elementary and chosen for the program that ran until 1972, from Grade 4 to 6. Major Works brought students together from across the school district to learn at an accelerated pace.

About a year ago, Thompson started tracking down his former classmates one by one for the reunion, set up for Saturday, June 2. More than a dozen of the former classmates got together the night before at Tap & Barrel.

“People were very emotional – lots of hugs. It was really amazing,” Thompson said.

Those attending the reunion came from across Canada – from Toronto, Calgary, Edmonton, Manitoba, the Interior of B.C. and Vancouver Island. Some still live in the Lower Mainland including in North Vancouver.

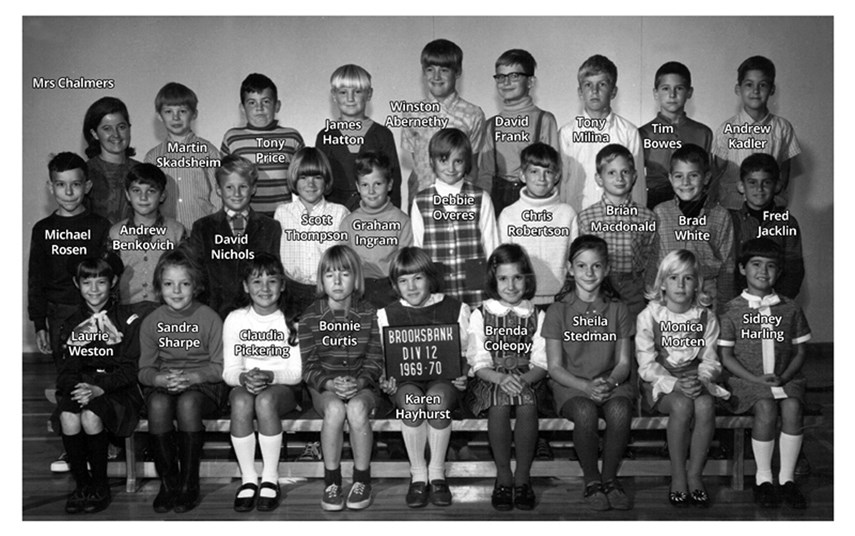

On Saturday, they were able to get into Brooksbank Elementary – where nothing had changed, Thompson said – and they were able to see the gym and take a photo in their Grade 4 classroom. Two of the original teachers attended the reunion, Margaret Chalmers and Sheila Gregson, both well into their retirement years.

After the official reunion, they didn’t want to part, and they spent the evening together reminiscing and catching up.

Thompson appreciated the accelerated academics at Major Works, and the group as a whole was motivated to learn, and most had an appreciation for knowledge.

“As soon as someone tells you you’re gifted, you try to live up to it,” Thompson said.

But the students were a small clique within the school and some students felt like outsiders – and some students outside the program teased them and called them the “major jerks.”

Thompson remembers their art class where they made clay bones and buried them in a grid pattern for another group to dig up like an archeological dig, after having learned about the work of Louis Leakey.

The students were taught subject matter beyond their grade-level curriculum and as soon as they mastered it, they moved on to the next level.

“In Grade 6, we eclipsed the teacher’s knowledge and the principal came and taught us advanced mathematics,” Thompson said.

After three years, the educational experiment was abandoned and students were sent back to regular classes. For Thompson, regular school was a breeze after working on academics way beyond his peers.

“I went back to Grade 7 and it was a big waste of time,” Thompson said.

He ended up being bumped up to Grade 8 and even then, school didn’t present any new challenges. “Most of what they were teaching, I had already learned – I was coasting,” he said.

Although he got labelled as a “smart-ass” back in the regular classroom, Thompson considers the entire experience as very positive.

“I’m glad I did it – I’d rather have done it than be with my peers,” he said. At 17, he was already at Langara and a few years later he started a sport fishing camp with his brother on Stuart Island. Thompson currently runs Think Tank Training Centre, a computer animation school in North Vancouver.

While this experiment ended abruptly, Thompson said he thinks a lot of what they were doing then is mirrored in the current curriculum, which focuses on individual learning styles.

Margaret Chalmers had just returned from a teacher exchange program to Scotland when she was put in charge of the Major Works class, and she thinks her experience abroad was the reason she was chosen.

“Educators at the time recognized children that were bright, and children with learning disabilities as well – we needed programs that would help them,” Chalmers said. The idea of Major Works, from her understanding, came from the school district.

“It was challenging – I was given the job but not given any information,” she said. “(In those days) teaching was whoever you had, you taught at that level.”

It turned out to be one of the most memorable teaching times for Chalmers, and she remembered the groups as “delightful.” The students were highly motived – some were “over-motivated, she said – and they gave a lot of input into what they wanted to learn.

“It was stimulating for me as a teacher,” she said. “I found out and did things I wouldn’t have done with a regular class.”

When she came to the reunion and reconnected with this group of “super, super young people,” she was moved to tears.

Fitting back into regular school

The students went back to their original schools when the gifted program ended in 1972. For some, it was a seamless transition; for others, it was hard fitting back in.

Many students remembered details about the classroom experiences and their teachers. But in responses to a survey that Thompson sent out in advance of the reunion, boredom was a common theme that came up when talking about regular classrooms after Major Works was disbanded. There was also a feeling of being different and standing out from the regular students.

For Andrew Kadler, memories from Major Works included carving a bear out of wood, creating Egyptian clay artifacts and burying them, having mortgage amortization explained to them in class, typesetting and publishing a newspaper, and tasting haggis. Returning to Grade 7 after the program ended was “really boring,” he said.

“I had my eyes opened in so many ways,” Kadler wrote about his experience at Brooksbank.

Fred Jacklin, who came from Maplewood Elementary, said in his survey response: “To be honest, I didn’t feel challenged again at school until I got to UBC.”

Jacklin added that he felt like an outsider in the Major Works program at Brooksbank Elementary.

“I honestly don’t remember interacting in any way with kids from outside of our class, but they would look at us like we were freaks or something,” he wrote.

When Chris Robertson returned to his regular classroom, it was “tough to fit in again and school was boring!!”

Dave Frank, who attended the reunion, said in his survey response that he would have been “bored out of his tree” if he had stayed at his home school, Queensbury Elementary.

“I have real concerns for the bright/creative students that are not challenged in our school system,” he explained in his survey answers. “They are equally important with the students that are challenged but that’s not a common belief.”

Returning to the regular program had social implications for Brad White.

“I had some good experiences, but the social cost of being in a ‘special’ program was too great,” he reported. “I missed out on experiences in high school because of my efforts to avoid any perception of being ‘gifted.’”

Monica Marten, who came from Brooksbank Elementary, said the program gave her confidence in her abilities, but it caused a rift with her brother.

“As life went on, I never questioned my ability to figure things out,” Marten wrote in the survey. But, she added, “I think it caused some jealousy in my non-MW friends. My brother recently told me that he got sick and tired of our mother always bragging about it.”

Winston Abernethy said he felt making a big deal about intelligence was a “fail” for him.

“It’s not very important I’ve since discovered,” he responded. “But I loved Ms. Chalmers and I loved the variety of experiences.”

For Shelagh Stedman Macdonald, being in a “gifted” class was difficult.

“I sensed it every time I was around the kids in the regular program,” she wrote in her survey response. “I hope some PhD candidate in psychology/sociology wrote a great dissertation on us.”